The History of Artificial Intelligence: From Turing to Today

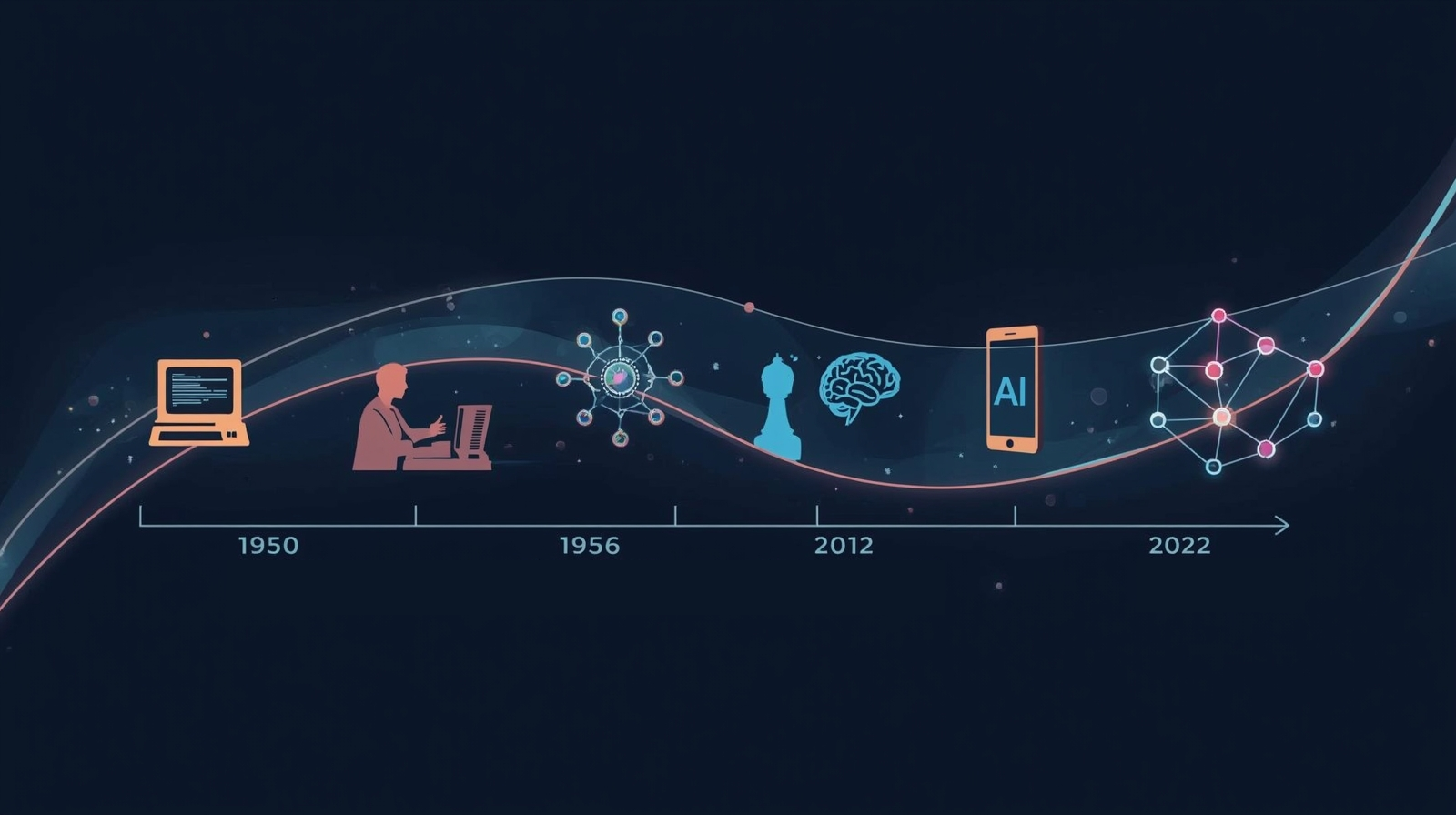

The History of Artificial Intelligence is more than a chronicle of technological advancement—it’s a story about humanity’s enduring fascination with creating intelligence beyond ourselves. From the moment Alan Turing posed the question “Can machines think?” in 1950, we’ve been on a journey that has transformed science fiction into everyday reality. Today, AI helps us navigate our commutes, diagnoses diseases, writes poetry, and even engages in philosophical debates. But understanding where we are today requires looking back at the visionaries, breakthroughs, and setbacks that shaped this extraordinary field.

As someone deeply invested in AI ethics and responsible innovation, I believe that understanding artificial intelligence history isn’t just academic—it’s essential for navigating our AI-powered present and shaping a safer, more equitable future. When we trace the path from Turing’s theoretical foundations to today’s generative AI systems, we gain perspective on both the immense possibilities and profound responsibilities that come with this technology.

What Is Artificial Intelligence? A Simple Definition

Before diving into the historical timeline, let’s establish a clear understanding of what we mean by artificial intelligence. At its core, AI refers to computer systems designed to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence. These tasks include learning from experience, recognizing patterns, understanding language, making decisions, and solving complex problems.

Think of AI as teaching machines to think, learn, and adapt—not by programming every possible scenario, but by enabling systems to improve through experience. When your email filter learns to identify spam more accurately over time, or when your music streaming service recommends songs that match your taste, that’s AI at work. The field encompasses everything from simple rule-based systems to sophisticated neural networks that can process information in ways loosely inspired by the human brain.

What makes AI particularly fascinating—and sometimes concerning—is its ability to evolve beyond its initial programming. Unlike traditional software that follows rigid instructions, AI systems can discover patterns, make predictions, and generate solutions that their creators never explicitly programmed. This capability has made AI both incredibly powerful and worthy of careful ethical consideration.

The Theoretical Foundations: Alan Turing’s Vision (1936-1950)

The History of Artificial Intelligence truly begins not in a laboratory but in the mind of a brilliant British mathematician named Alan Turing. In 1936, while most people were focused on economic recovery from the Great Depression, Turing published a paper that would fundamentally change our understanding of computation itself. His concept of the “universal machine”—later known as the Turing machine—established the theoretical foundation for all modern computing.

But Turing’s most direct contribution to AI came in 1950 with his groundbreaking paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Rather than getting lost in philosophical debates about consciousness, Turing proposed a practical test: if a machine could engage in conversation so convincingly that a human evaluator couldn’t reliably distinguish it from another human, we should consider that machine intelligent. This became known as the Turing Test, and it remains an influential (if controversial) benchmark in AI discussions today.

What makes Turing’s vision particularly remarkable is that he imagined intelligent machines before the technology to build them even existed. He was asking profound questions about machine learning and artificial minds when computers were still room-sized calculators that could barely perform basic arithmetic. His work gave researchers permission to ask, “Can machines think?”—a question that would drive decades of innovation.

Turing’s tragic death in 1954 came just as the field he helped inspire was about to explode into existence. His legacy, however, would influence every AI researcher who followed, reminding us that the most powerful innovations often begin with a single, audacious question.

The Birth of AI as a Field: The Dartmouth Conference (1956)

The summer of 1956 marked a pivotal moment when artificial intelligence transitioned from theoretical speculation to an organized field of research. At Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, a group of brilliant minds gathered for what would become known as the Dartmouth Workshop. The conference organizers—John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon—proposed an ambitious summer research project based on “the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

It was McCarthy who coined the term “artificial intelligence” for this conference, giving the field its official name. This wasn’t just a semantic choice—it was a declaration of intent. These researchers weren’t interested in building better calculators; they wanted to create machines that could genuinely think, learn, and reason.

The Dartmouth Conference brought together researchers who would shape AI development for decades. They discussed neural networks, natural language processing, and machine learning—concepts that seemed almost magical in an era when computers still used punch cards. The optimism was intoxicating. Many participants believed that machines with human-level intelligence would emerge within a generation.

While that prediction proved wildly optimistic, the Dartmouth Conference achieved something perhaps more important: it created a community. Researchers from different institutions and backgrounds found common cause, shared terminology, and collective purpose. The field of AI officially existed, complete with research agendas, funding proposals, and dreams of revolutionary breakthroughs.

The Era of Optimism and Early Programs (1956-1974)

Following Dartmouth, AI research entered what historians now call its first “Golden Age.” The late 1950s and 1960s were characterized by remarkable enthusiasm and surprising early successes. Researchers developed programs that could prove mathematical theorems, play checkers at a competitive level, and even understand simple English sentences. Each breakthrough fueled the belief that general artificial intelligence was just around the corner.

One of the most impressive early achievements was the Logic Theorist, developed by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon in 1956. This program could prove mathematical theorems from Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s “Principia Mathematica”—sometimes discovering proofs more elegant than the originals. For the first time, a machine had demonstrated something that looked remarkably like human reasoning.

ELIZA, created by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT in 1966, represented another fascinating milestone. This simple natural language processing program simulated a psychotherapist by reflecting users’ statements back to them with therapeutic-sounding responses. What stunned Weizenbaum was how emotionally people responded to ELIZA, attributing understanding and empathy to what was essentially a pattern-matching script. This unexpected human response to AI would foreshadow ethical questions we still grapple with today.

However, beneath this optimism, fundamental challenges were brewing. Early AI systems were brittle—they worked well in controlled environments but failed catastrophically when faced with real-world complexity. The computational power required for more sophisticated AI remained far beyond what available technology could provide. And perhaps most significantly, researchers were beginning to realize that replicating human intelligence was vastly more complex than they had initially imagined.

The First AI Winter: Disillusionment and Reduced Funding (1974-1980)

The enthusiastic predictions of the 1960s crashed against the harsh reality of computational limits and unfulfilled promises. By the mid-1970s, the history of artificial intelligence entered its first “AI Winter”—a period of drastically reduced funding, abandoned projects, and widespread skepticism about the field’s future.

The turning point came with two influential critical reports. In 1973, British mathematician Sir James Lighthill published a report for the UK Science Research Council that devastatingly criticized AI research. Lighthill argued that AI had failed to deliver on its grandiose promises and that most achievements were essentially “combinatorial explosions” that couldn’t scale to real-world problems. His report led to significant cuts in AI research funding across Britain.

Similarly, in 1969, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published “Perceptrons,” which mathematically demonstrated fundamental limitations in simple neural networks (specifically, single-layer perceptrons). While the book made important theoretical contributions, it had an unintended chilling effect on neural network research that would last nearly two decades. Many researchers abandoned neural network approaches, believing them to be fundamentally limited.

The practical challenges were equally daunting. Expert systems—programs designed to replicate human expert knowledge in narrow domains—showed some promise but proved expensive to develop and difficult to maintain. They couldn’t handle uncertainty, learn from experience, or adapt to new situations. The gap between laboratory demonstrations and commercially viable products remained frustratingly wide.

Funding agencies, burned by years of unfulfilled promises, became skeptical. Research grants dried up. University AI programs closed or merged with other departments. Many talented researchers left the field entirely, pursuing careers in more stable areas of computer science. The term “artificial intelligence” itself became almost taboo in funding proposals—researchers learned to describe their work using less controversial terminology.

Yet this winter wasn’t entirely barren. Some researchers continued working on fundamental problems, developing theoretical frameworks that would prove crucial when AI eventually revived. The field learned hard lessons about the importance of realistic expectations, rigorous evaluation, and understanding fundamental computational limits. Sometimes progress requires consolidation as much as innovation.

Expert Systems and the Second Wave (1980-1987)

Like spring following winter, AI experienced a dramatic revival in the early 1980s, driven by a technology that seemed to bridge the gap between academic research and commercial application: expert systems. These programs captured the knowledge of human experts in specific domains—medical diagnosis, chemical analysis, and computer configuration—and made that expertise available to non-experts.

The success story that launched this revival was XCON (eXpert CONfigurer), developed by Digital Equipment Corporation in 1980. XCON helped configure computer systems by determining the optimal combination of components for customer orders. By 1986, it was saving DEC an estimated $40 million annually. This wasn’t theoretical research—it was practical, profit-generating AI that executives could understand and investors could support.

Japan’s announcement of their ambitious Fifth Generation Computer Project in 1981 sent shockwaves through the global AI community. Japan planned to invest $850 million over ten years to develop intelligent computers based on logic programming and knowledge representation. The project aimed to leapfrog Western computing leadership, creating machines that could reason, learn, and understand natural language. Whether from genuine concern or competitive pressure, this announcement triggered massive new investments in AI research across the United States and Europe.

Companies rushed to develop their own expert systems. By 1985, AI had become a billion-dollar industry. Specialized hardware—AI workstations and LISP machines—were developed specifically to run expert systems efficiently. Universities reinstated AI programs. The field’s credibility was restored, and the future again looked promising.

Expert systems worked by encoding human knowledge as “if-then” rules. For example, a medical diagnosis system might have rules like, “IF patient has fever AND cough AND chest pain, THEN consider pneumonia.” Thousands of such rules, combined with inference engines to apply them, could replicate expert decision-making in narrow domains. The approach was transparent—you could trace exactly why the system reached a particular conclusion—which made it particularly appealing for applications requiring explanations.

However, expert systems had fundamental limitations that would eventually contribute to another AI winter. They required extensive manual knowledge engineering—domain experts working with AI specialists to codify knowledge as rules. This process was time-consuming, expensive, and never complete. Expert systems couldn’t learn from experience or adapt to changing conditions. They performed well within their narrow domains but failed spectacularly when faced with problems outside their programmed knowledge.

The brittleness of expert systems, combined with the failure of Japan’s Fifth Generation Project to deliver on its ambitious promises, set the stage for the second AI winter. But before that chill set in, these systems proved something important: AI could deliver real business value when properly focused on specific, well-defined problems.

The Second AI Winter and Neural Network Renaissance (1987-1993)

By the late 1980s, the limitations of expert systems became painfully apparent. The second AI winter descended as companies discovered that maintaining and updating these systems was prohibitively expensive. Many expert systems became obsolete as the domains they covered evolved. The specialized hardware manufacturers went bankrupt or pivoted to other markets. Once again, “artificial intelligence” became a term associated with hype and disappointment.

Yet during this cold period, a different approach was quietly gaining momentum. Researchers returned to neural networks—the brain-inspired computing models that had been largely abandoned after Minsky and Papert’s critique. The key breakthrough came in 1986 when David Rumelhart, Geoffrey Hinton, and Ronald Williams published their work on backpropagation, an algorithm that could train multi-layer neural networks by adjusting connection weights based on error feedback.

Backpropagation overcame the limitations that Minsky and Papert had identified in simple perceptrons. Multi-layer networks could learn complex patterns and relationships that single-layer networks could not. This wasn’t just a theoretical advance—researchers began achieving practical successes in pattern recognition, speech processing, and other challenging tasks.

Yann LeCun’s work on convolutional neural networks at Bell Labs in 1989 demonstrated that neural networks could learn to recognize handwritten digits with remarkable accuracy. His LeNet system could read zip codes on mail envelopes, showing that neural network research could solve real-world problems with commercial applications. This work laid crucial groundwork for the deep learning revolution that would follow decades later.

The neural network renaissance didn’t immediately thaw the AI winter—funding remained scarce and skepticism widespread—but it established an alternative path forward. Rather than trying to explicitly program intelligence through rules and logic, neural networks learned patterns from data. This machine learning approach would eventually transform not just AI, but the entire technology landscape.

Machine Learning Takes Center Stage (1993-2011)

As the 1990s progressed, the history of artificial intelligence shifted from knowledge representation to data-driven learning. The focus moved away from trying to explicitly encode intelligence and toward systems that could extract patterns and insights from data. This period saw machine learning emerge from a specialized research area to become the dominant paradigm in AI.

Several factors converged to make this transition possible. First, increasing computational power made it feasible to train more complex models on larger datasets. Second, the growth of the internet and digital data collection meant that massive datasets became available for training. Third, algorithmic improvements in machine learning techniques—including support vector machines, random forests, and improved neural network training methods—delivered consistently impressive results.

The 1997 chess match between IBM’s Deep Blue and world champion Garry Kasparov represented a watershed moment for AI’s public perception. When Deep Blue won the rematch, defeating the reigning human champion, it demonstrated that machines could outperform humans in tasks requiring strategic thinking and complex evaluation. While Deep Blue used brute-force computation rather than the neural networks that would dominate later AI, the victory showed that AI could tackle problems previously thought to require uniquely human capabilities.

During this period, practical machine learning applications began transforming everyday technology. Email spam filters learned to identify unwanted messages. Recommendation systems learned user preferences to suggest products, movies, or music. Search engines like Google used machine learning to rank results more effectively. These weren’t science fiction applications—they were solving real problems that billions of people encountered daily.

Statistical machine learning methods proved particularly successful. Support vector machines, developed by Vladimir Vapnik and colleagues, could classify data by finding optimal boundaries between categories. Random forests combined multiple decision trees to make robust predictions. These approaches worked reliably across diverse applications, from credit card fraud detection to medical diagnosis support.

The field also made significant progress in natural language processing. Statistical language models could predict word sequences, enabling better machine translation and speech recognition. IBM’s Watson system, which famously won the quiz show Jeopardy! in 2011, showcased how multiple AI techniques—natural language understanding, information retrieval, and probabilistic reasoning—could be integrated to answer complex questions.

Despite these advances, AI still faced significant limitations. Most systems required extensive feature engineering—human experts manually designing what patterns the system should look for. Machine learning worked well for specific tasks but couldn’t generalize across different domains. Creating a system that could excel at multiple unrelated tasks remained elusive. The dream of artificial general intelligence—AI with human-like flexibility and broad capabilities—still seemed distant.

The Deep Learning Revolution (2012-Present)

In 2012, the history of artificial intelligence reached an inflection point that would accelerate the field into its current explosive growth. The catalyst was a dramatic demonstration at the ImageNet competition, where a deep learning system called AlexNet, developed by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton, achieved error rates far below any previous image recognition system. This breakthrough proved that deep neural networks—networks with many layers of abstraction—could outperform traditional machine learning approaches when given sufficient data and computational power.

What made this revolution possible? Three critical ingredients came together: big data, powerful GPUs originally designed for gaming, and algorithmic improvements in training deep neural networks. Researchers discovered how to train networks with dozens or even hundreds of layers, enabling systems to learn hierarchical representations of increasing abstraction. Early layers might detect edges and textures; middle layers might recognize shapes and object parts; deeper layers could identify complex objects and concepts.

The implications were profound and immediate. Within a few years, deep learning transformed field after field. Computer vision systems achieved superhuman performance on many tasks. Speech recognition improved dramatically—voice assistants like Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant became genuinely useful. Machine translation improved to the point where neural machine translation could handle entire documents with reasonable accuracy.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) revolutionized image processing, enabling applications from medical image analysis to autonomous vehicle perception. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their more sophisticated cousin, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, excelled at processing sequential data like text and speech. These architectures could capture complex temporal patterns that earlier approaches missed.

The 2016 match between Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo and world champion Go player Lee Sedol represented another milestone moment. Go, an ancient Chinese board game, has more possible positions than atoms in the observable universe, making it far more complex than chess. Yet AlphaGo won decisively, using a combination of deep neural networks and reinforcement learning. The victory demonstrated that AI could master tasks requiring intuition, strategy, and creative thinking—qualities many believed were uniquely human.

The field of reinforcement learning—where AI agents learn through trial and error to maximize rewards—also flourished during this period. DeepMind’s agents learned to play dozens of Atari games at superhuman levels using only the game pixels as input. The principles behind these breakthroughs are now being applied to robotics, resource optimization, and complex decision-making in business and science.

The Transformer Architecture and Large Language Models

In 2017, researchers at Google introduced a neural network architecture called the Transformer in their paper “Attention Is All You Need.” This architecture would prove to be as revolutionary as the invention of the backpropagation algorithm decades earlier. Transformers used a mechanism called “attention” to process sequences of data, enabling them to capture long-range dependencies and relationships far more effectively than previous approaches.

The impact of Transformers became clear with the development of large language models—AI systems trained on vast amounts of text data to understand and generate human language. OpenAI’s GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) series demonstrated increasingly impressive language capabilities. GPT-2, released in 2019, could write coherent paragraphs on diverse topics. GPT-3, released in 2020 with 175 billion parameters, showed abilities that seemed to approach general intelligence in the language domain.

These models demonstrated remarkable versatility. Without task-specific training, they could translate languages, answer questions, write poetry, explain complex concepts, and even generate computer code. The approach was deceptively simple: train a massive neural network to predict the next word in a sentence, using billions of examples from the internet. Through this process, the models appeared to develop rich representations of language, knowledge, and reasoning.

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), developed by Google in 2018, took a different approach by reading text bidirectionally to better understand context. BERT and its variants dramatically improved performance on natural language understanding tasks, powering improvements in search engines, chatbots, and document analysis systems.

The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 marked another pivotal moment in public AI awareness. This conversational AI system, based on GPT-3.5 and later GPT-4, made advanced natural language AI accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Within months, millions of people were using ChatGPT for everything from writing assistance to coding help to philosophical discussions. The system’s ability to engage in coherent, contextually appropriate conversations amazed users and sparked intense debate about AI’s capabilities and implications.

GPT-4, released in March 2023, demonstrated multimodal capabilities—processing both text and images—and showed improved reasoning abilities. It passed professional exams at human-level performance, from the bar exam to AP tests in multiple subjects. While debates continue about what these capabilities truly represent, there’s no doubt that large language models have brought AI into mainstream consciousness like never before.

Other tech companies rapidly developed competing systems. Google’s Bard (later renamed Gemini), Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft’s integration of GPT-4 into Bing, and numerous open-source alternatives like Meta’s Llama models created an explosion of generative AI applications. These systems could generate not just text but also images (DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion), music, video, and even 3D models.

The transformer architecture’s success extended beyond language. Vision Transformers applied the same principles to image recognition. Multi-modal transformers could process multiple types of data simultaneously, understanding relationships between text, images, and other inputs. The architecture proved remarkably versatile and scalable—simply making models larger and training them on more data consistently improved performance.

Current State: AI in 2024-2025

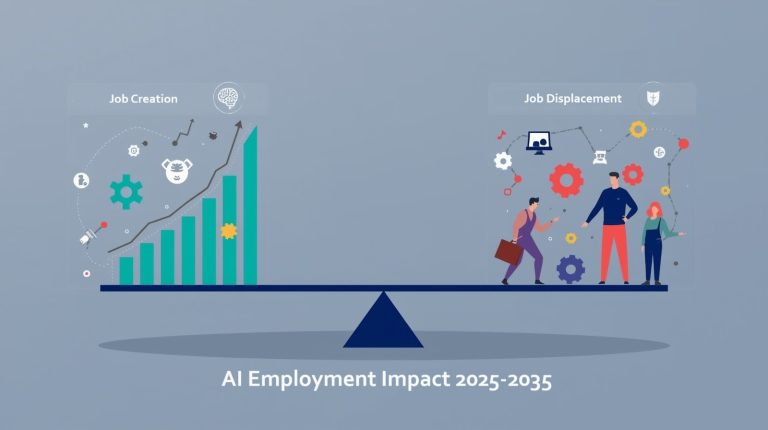

As we move through 2025, the history of artificial intelligence has reached a moment of unprecedented capability and complexity. AI systems are now integral to global infrastructure, embedded in systems from financial markets to power grids to healthcare delivery. The question is no longer whether AI can perform intelligent tasks, but how we should deploy these powerful capabilities responsibly.

Current AI excels at specialized tasks that involve pattern recognition, language processing, and generation. Computer vision systems can detect cancer in medical images with accuracy matching or exceeding human specialists. Natural language processing enables real-time translation across dozens of languages, making global communication more accessible. AI drives autonomous vehicles, optimizes supply chains, discovers new drugs, and assists creative professionals in generating art, music, and written content.

The integration of AI into professional workflows has accelerated dramatically. Software developers use AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot to write code more efficiently. Writers use AI tools for brainstorming, editing, and research. Designers use generative AI to explore visual concepts rapidly. These applications don’t replace human expertise—they augment it, handling routine tasks and enabling professionals to focus on higher-level creative and strategic work.

Artificial intelligence research continues advancing on multiple fronts. Researchers are working on more efficient training methods that require less computational power and data. Techniques like transfer learning allow models trained on one task to adapt quickly to related tasks. Few-shot and zero-shot learning enable systems to perform tasks with minimal examples or even just descriptions of what’s needed.

The field is also grappling with fundamental questions about AI’s limitations and risks. Current systems can produce plausible-sounding text that contains errors or fabrications—a phenomenon called “hallucination.” They can amplify biases present in training data, potentially perpetuating or exacerbating societal inequities. Large models require enormous computational resources, raising environmental concerns about their energy consumption and carbon footprint.

AI safety has emerged as a critical research area. How do we ensure AI systems behave as intended? How can we make them more comprehensible so we understand why they make particular decisions? How do we prevent misuse for generating misinformation, invading privacy, or causing other harms? These aren’t merely theoretical concerns—they’re urgent practical challenges as AI becomes more powerful and widely deployed.

Governance and regulation are evolving to address these challenges. The European Union’s AI Act represents the first comprehensive legal framework for AI regulation, categorizing AI systems by risk level and imposing requirements for transparency, testing, and accountability. Other jurisdictions are developing their own approaches, balancing innovation with safety and ethical considerations.

Despite tremendous progress, important limitations remain. Current AI lacks genuine understanding—it processes patterns without comprehending meaning the way humans do. Systems trained on one type of task can’t easily transfer that knowledge to radically different domains. AI can’t explain its reasoning in truly transparent ways, making it challenging to trust in high-stakes applications. And perhaps most fundamentally, we’re nowhere near artificial general intelligence—AI that can flexibly handle any intellectual task a human can perform.

Key Lessons from AI’s Historical Journey

Reflecting on decades of AI development reveals patterns and insights crucial for understanding our current moment and navigating the future responsibly. These lessons emerge not from theory but from the field’s lived experience—its breakthroughs, failures, winters, and renaissances.

Progress is rarely linear. The history of AI isn’t a steady upward trajectory but rather a series of waves—periods of intense optimism and advancement followed by disappointment and retrenchment. Each AI winter taught the field hard lessons about managing expectations, focusing on solvable problems, and building on solid theoretical foundations. Understanding this pattern helps us approach current AI capabilities with appropriate perspective: neither dismissing concerns as hype nor assuming unlimited progress.

Breakthroughs often come from unexpected directions. Many of AI’s most significant advances—backpropagation, deep learning, transformers—were initially dismissed or overlooked. Neural networks fell out of favor for decades before becoming the dominant paradigm. The lesson here is humility: today’s rejected approaches might be tomorrow’s breakthroughs, and today’s dominant methods will eventually be superseded.

Data, computation, and algorithms must align. The deep learning revolution succeeded not because of algorithmic breakthroughs alone, but because massive datasets, powerful GPUs, and improved training methods converged simultaneously. This interdependence reminds us that AI progress depends on multiple enabling factors working together. It also means that limitations in any area—available data, computational resources, or algorithmic understanding—can constrain overall progress.

Narrow AI works; general AI remains elusive. Nearly every practical AI success involves systems designed for specific, well-defined tasks. Chess programs play chess brilliantly but can’t diagnose diseases. Language models excel at text generation but struggle with physical reasoning. Despite decades of effort, we still lack AI with human-like flexibility to learn any intellectual task. This suggests that achieving artificial general intelligence may require fundamentally different approaches, not just scaling up current methods.

Ethical considerations grow with capability. As AI systems become more powerful, the ethical questions become more urgent. Early AI programs raised few ethical concerns—they were too limited to cause significant harm. Today’s systems can influence elections, make consequential decisions about people’s lives, and potentially be weaponized. The history of AI teaches us that we must develop ethical frameworks, safety measures, and governance structures in parallel with technical capabilities, not as afterthoughts.

Transparency and trust matter increasingly. Early AI systems could explain their reasoning—you could trace through the rules an expert system applied. Modern deep learning systems are often “black boxes” whose internal decision-making processes remain opaque even to their creators. This lack of interpretability becomes problematic in high-stakes domains like healthcare, criminal justice, and finance. Building trustworthy AI requires not just accuracy but also explainability.

How to Engage Responsibly with AI Today

Understanding the history of artificial intelligence isn’t merely academic—it provides crucial context for navigating our AI-saturated present. As someone committed to safe and ethical AI use, I believe everyone should develop informed perspectives on how to engage with these powerful technologies.

Start with education and experimentation. The best way to understand AI’s capabilities and limitations is direct experience. Experiment with accessible AI tools like ChatGPT, image generators, or coding assistants. Notice where they excel and where they fail. This hands-on experience builds intuition about what AI can and cannot do, helping you develop realistic expectations and identify potential risks.

Verify AI outputs carefully. AI systems, particularly large language models, can generate plausible-sounding content that contains factual errors, outdated information, or complete fabrications. Never treat AI-generated content as inherently reliable. Cross-check important information against authoritative sources. Use AI as a starting point for research or creativity, not as the final word.

Understand privacy implications. When you interact with AI systems, consider what data you’re sharing. Many commercial AI services use user inputs to improve their models. Be cautious about sharing sensitive personal information, proprietary business data, or confidential details. Review privacy policies and terms of service. For sensitive applications, consider using systems that explicitly don’t train on user data or deploy AI models locally on your own devices.

Recognize and challenge biases. AI systems learn from training data that often reflects existing societal biases regarding race, gender, age, and other characteristics. Be alert for biased outputs—whether in generated text, image search results, or automated decisions. When you encounter biased AI behavior, report it to the system developers and advocate for more equitable AI development practices.

Use AI as an augmentation tool, not replacement. The most successful AI applications enhance human capabilities rather than attempting to replace human judgment entirely. Use AI to handle routine tasks, generate initial drafts, or explore possibilities, but retain human oversight for final decisions, especially in consequential domains. This approach leverages AI’s strengths while mitigating its weaknesses.

Stay informed about AI developments. The field evolves rapidly—new capabilities, risks, and applications emerge constantly. Follow reputable sources covering AI research, ethics, and policy. Engage in community discussions about AI’s societal impacts. Understanding the trajectory of AI development helps you anticipate changes and advocate for responsible deployment.

Support ethical AI development. As consumers and citizens, we influence how AI develops through our choices and voices. Support companies and organizations prioritizing transparency, fairness, and user rights. Advocate for thoughtful AI regulation that balances innovation with safety. Participate in public discussions about AI governance. The future of AI depends not just on researchers and corporations, but on informed public engagement.

Prepare for ongoing change. AI will continue evolving, bringing new applications and challenges we can’t fully anticipate. Develop adaptability—the ability to learn new tools, adjust to changing workflows, and think critically about technological change. Historical perspective shows that AI’s trajectory includes both tremendous benefits and significant risks. Navigating this future successfully requires active, informed engagement rather than passive acceptance or fearful rejection.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next?

As we consider the future trajectory of artificial intelligence, historical perspective suggests both caution about predictions and excitement about possibilities. Every generation of AI researchers has underestimated the difficulty of achieving certain milestones while being surprised by unexpected breakthroughs. That pattern will likely continue.

Several frontiers appear particularly promising for near-term progress. Multimodal AI—systems that seamlessly integrate text, images, audio, video, and other data types—will likely become more sophisticated, enabling richer human-AI interaction. We’re already seeing early versions in systems like GPT-4 that process both text and images, but future systems will likely integrate many more modalities with deeper understanding.

AI-assisted scientific discovery represents another exciting frontier. AI systems are already contributing to drug discovery, materials science, climate modeling, and fundamental physics research. As these tools improve, they could accelerate scientific progress across disciplines, helping us address urgent challenges from disease to climate change to clean energy.

Personalized AI assistants that understand individual contexts, preferences, and needs will likely become more capable and widespread. Rather than one-size-fits-all models, we may see AI systems that adapt deeply to individual users while respecting privacy—learning your working style, communication preferences, and domain expertise to provide truly customized support.

The push toward more efficient AI will likely yield important advances. Current large models require enormous computational resources, limiting their accessibility and environmental sustainability. Research into more efficient architectures, better training methods, and hardware optimized for AI workloads could democratize access to powerful AI capabilities while reducing environmental impact.

Robotic systems integrating advanced AI will probably make significant strides. Combining improved computer vision, natural language understanding, and physical reasoning could enable robots that navigate complex real-world environments and perform useful tasks—from eldercare to disaster response to space exploration.

However, significant challenges remain. Achieving more robust, reliable AI that doesn’t produce hallucinations or fail unpredictably requires fundamental advances in how we train and evaluate systems. Building interpretable AI that can explain its reasoning in ways humans can understand and verify remains largely unsolved. Ensuring AI systems align with human values and intentions becomes more critical—and more difficult—as capabilities increase.

The question of artificial general intelligence continues to divide researchers. Some believe we’re on a clear path toward human-level AI through scaling current approaches. Others argue that fundamental breakthroughs in understanding intelligence itself will be required. Historical precedent suggests that major leaps often come from unexpected directions, so humility about predictions seems warranted.

What seems certain is that AI will become increasingly integrated into the fabric of society. The question isn’t whether AI will transform work, education, healthcare, entertainment, and other domains, but how we can guide that transformation toward beneficial outcomes while mitigating risks and ensuring equitable access to benefits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Conclusion: Learning from History to Shape the Future

The History of Artificial Intelligence is ultimately a human story—a chronicle of ambition, creativity, disappointment, perseverance, and breakthrough. From Turing’s theoretical vision through the winters of skepticism to today’s generative AI revolution, the field has been shaped by brilliant individuals asking audacious questions and refusing to accept that intelligence is exclusively biological.

As we stand at this pivotal moment, with AI capabilities advancing faster than most anticipated, the lessons of history become more relevant than ever. We’ve learned that progress comes in waves, that narrow applications work while general intelligence remains elusive, and that ethical considerations must evolve alongside technical capabilities. We’ve discovered that breakthroughs often emerge from unexpected directions and that the gap between laboratory demonstrations and real-world deployment is frequently larger than it appears.

Understanding this history empowers us to engage with AI more thoughtfully and effectively. Rather than viewing AI as either a miraculous solution or an existential threat, historical perspective reveals it as a powerful tool whose impacts depend fundamentally on how we choose to develop and deploy it. The scientists, engineers, policymakers, and users of today will determine whether AI amplifies the best of human capability or exacerbates our worst tendencies.

The future of AI remains unwritten. Will we develop systems that augment human creativity and problem-solving while respecting autonomy and dignity? Will we ensure that AI’s benefits are broadly shared rather than concentrated among a privileged few? Will we build robust safeguards before deploying increasingly powerful systems? These questions don’t have predetermined answers—they depend on choices we make collectively in the coming years.

My hope, grounded in commitment to ethical technology use, is that we can learn from AI’s history to navigate its future more wisely. That means maintaining healthy skepticism about grandiose claims while remaining open to genuine breakthroughs. It means prioritizing safety, transparency, and human welfare over pure capability or profit. It means ensuring diverse voices shape AI’s development, not just technical experts and corporate leaders.

The journey from Turing’s theoretical machines to today’s sophisticated neural networks has been remarkable, but it’s far from complete. As AI continues evolving, each of us has a role to play—whether as users demanding ethical practices, professionals integrating AI thoughtfully into our work, citizens advocating for wise governance, or simply informed individuals asking critical questions about the technology shaping our world.

The history of artificial intelligence teaches us that the future is neither predetermined nor entirely within our control, but that informed, ethical engagement makes a profound difference. By understanding where we’ve been, we can better navigate where we’re going—embracing AI’s potential while staying vigilant about its risks, and ensuring that as these powerful systems become more capable, they remain aligned with human values and serve the broader good.

Now is the time to learn, engage, and help shape AI’s next chapter. The history we’ve explored isn’t just about past achievements—it’s a foundation for building the future we want to see.

References:

Turing, A.M. (1950). “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Mind, Volume 59, Issue 236.

McCarthy, J., Minsky, M., Rochester, N., & Shannon, C. (1955). “A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence.”

Rumelhart, D.E., Hinton, G.E., & Williams, R.J. (1986). “Learning representations by back-propagating errors.” Nature 323.

LeCun, Y., et al. (1989). “Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition.” Neural Computation.

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G.E. (2012). “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.”

Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). “Attention Is All You Need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Stanford University (2024). “AI Index Report.” Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2021). “Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach” (4th Edition). Pearson.

Bostrom, N. (2014). “Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies Oxford University Press.

About the Author

Nadia Chen is an expert in AI ethics and digital safety with over a decade of experience helping individuals and organizations use artificial intelligence responsibly. With a background spanning computer science and philosophy, Nadia bridges the technical and human dimensions of AI, making complex technologies accessible to non-technical audiences. She has advised educational institutions, nonprofits, and technology companies on ethical AI deployment and has developed digital safety curricula used by thousands of learners worldwide.

Nadia’s work focuses on empowering people to use AI confidently while understanding its limitations and risks. She believes that AI literacy shouldn’t be confined to technical experts—everyone affected by these technologies deserves to understand how they work and how to use them safely. Through her writing, workshops, and advocacy, Nadia helps build a future where AI enhances human capabilities without compromising privacy, fairness, or autonomy.

When not writing about AI ethics, Nadia enjoys hiking, reading science fiction that explores human-technology relationships, and volunteering with organizations that promote digital literacy in underserved communities. She holds degrees in computer science and ethics from leading universities and continues to research how emerging technologies can be developed and deployed in ways that prioritize human well-being.