Types of AI: From Narrow to General

Types of AI might sound like something from a science fiction novel, but artificial intelligence is already woven into the fabric of our daily lives. From the moment your smartphone alarm wakes you up to the personalized recommendations you see while shopping online, AI is quietly working behind the scenes. But here’s what most people don’t realize: not all AI is created equal. Understanding the different types of AI isn’t just fascinating—it’s essential for navigating our increasingly automated world safely and effectively.

As someone who focuses on AI ethics and digital safety, I’ve seen firsthand how misconceptions about AI can lead to both unrealistic fears and misplaced trust. We’re going to demystify the landscape of artificial intelligence together, exploring everything from the narrow AI that powers your voice assistant to the theoretical superintelligence that keeps researchers awake at night. Whether you’re a student, professional, or simply curious about technology, this guide will help you understand where AI stands today and where it’s heading tomorrow.

Understanding the Fundamental Categories of Artificial Intelligence

Before we dive into specific types, let me share something important: AI classification isn’t as straightforward as labeling fruits at a market. Researchers categorize AI systems in multiple ways—by capability, by functionality, and by learning method. Think of it like describing vehicles: you can classify them by size (cars, trucks, buses), by power source (gas, electric, hybrid), or by purpose (transportation, recreation, work). The same principle applies to AI.

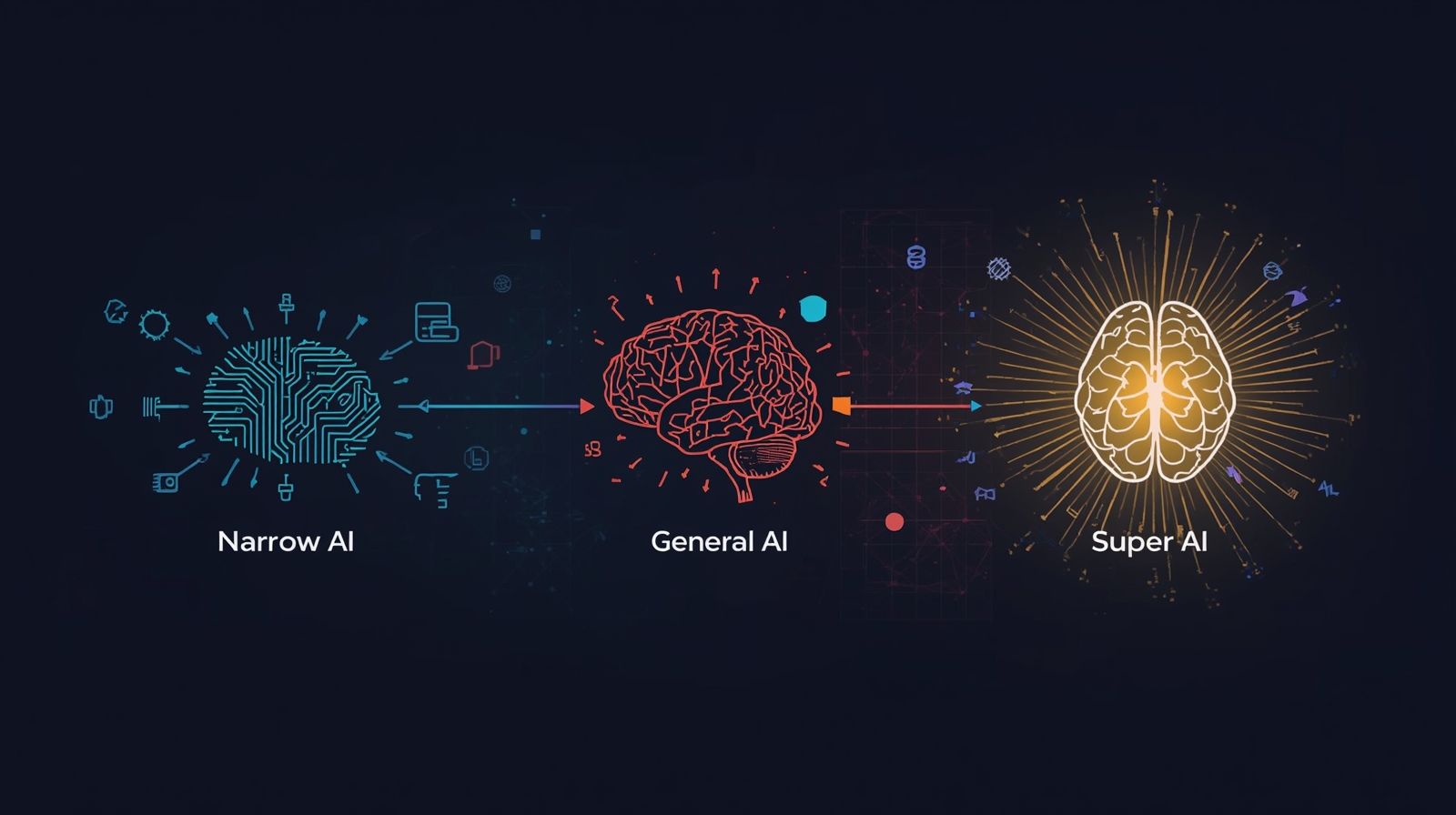

The most common framework divides AI into three broad categories based on capability: Narrow AI (also called Weak AI or ANI), General AI (also known as Strong AI or AGI), and Super AI (ASI). These categories represent increasing levels of intelligence and autonomy. But there’s another classification system based on functionality that includes reactive machines, limited memory systems, theory of mind AI, and self-aware AI. We’ll explore both frameworks because understanding them gives you a complete picture of the AI landscape.

Narrow AI (ANI): Defining Characteristics and Real-World Examples

Narrow AI is the only type of artificial intelligence that exists today, and it’s everywhere. When I explain this to non-technical friends, I describe it as AI with one job and one job only. Unlike humans who can switch from cooking breakfast to solving math problems to playing music, narrow AI excels at specific tasks but can’t transfer that expertise elsewhere.

Your smartphone’s face recognition system is brilliant at identifying faces but couldn’t drive a car. Netflix’s recommendation algorithm knows your viewing preferences inside out but couldn’t diagnose a medical condition. Chess-playing AI like Deep Blue can defeat world champions but can’t even play checkers. This specialization is both narrow AI’s greatest strength and its fundamental limitation.

What makes narrow AI so prevalent is its practical reliability. These systems operate within carefully defined parameters, making them predictable and trustworthy for specific applications. When you use voice recognition to dictate a message, narrow AI converts your speech to text with impressive accuracy—but it doesn’t understand what you’re saying, feel emotions about your message, or think about anything beyond its programmed task.

The real-world applications are staggering. Narrow AI powers email spam filters, language translation services, autonomous vehicle navigation systems, fraud detection in banking, medical image analysis, smart home devices, virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, social media content recommendations, and countless other tools we use daily. Each one brilliant within its domain, each one blind to everything else.

From an ethical standpoint, narrow AI presents manageable challenges. Since these systems operate within defined boundaries, we can test them thoroughly, understand their limitations, and implement safeguards. The key is never expecting more from narrow AI than it’s designed to deliver—a lesson many users learn the hard way when they trust these systems beyond their capabilities.

General AI (AGI): The Quest for Human-Level Intelligence in Machines

General AI represents the holy grail of artificial intelligence research—and it doesn’t exist yet. When we talk about AGI, we’re describing hypothetical AI systems that would possess human-like cognitive abilities across the board. Imagine a machine that could learn to play piano, understand Shakespeare, solve mathematical proofs, empathize with emotional struggles, and debate philosophy—all without being specifically programmed for each task.

The distinction between narrow and general AI is profound. While narrow AI mimics human capabilities in isolated domains, general AI would replicate the flexibility, adaptability, and transfer learning that defines human intelligence. If you learned to ride a bicycle, you’d find it easier to learn to ride a motorcycle. AGI would demonstrate that same ability to apply knowledge from one domain to enhance learning in another.

Why hasn’t AGI been achieved despite decades of research? The challenge is exponentially more complex than most people realize. Human intelligence involves consciousness, emotional understanding, creativity, common sense reasoning, and the ability to learn from minimal examples—capabilities we still don’t fully understand in ourselves, let alone know how to recreate artificially. Current AI systems require massive datasets and extensive training for narrow tasks; humans learn to recognize objects with just a few examples and understand context intuitively.

The timeline for achieving general AI is hotly debated. Some researchers believe we’re decades away, others suggest it may arrive within our lifetimes, and some question whether it’s possible at all with current computational approaches. What’s certain is that creating AGI requires breakthrough innovations in computer science, neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and philosophy.

From a safety perspective, AGI presents unprecedented challenges. Unlike narrow AI with defined boundaries, general intelligence could potentially act in unpredictable ways, pursue goals we didn’t intend, or make decisions we can’t fully anticipate. This is why AI safety research has become so critical—we need to solve alignment problems before AGI becomes reality, not after.

Super AI (ASI): Exploring the Hypothetical Realm of Superintelligence

If general AI seems far-fetched, Super AI ventures into territory that sounds like pure speculation—yet it’s taken seriously by leading AI researchers and organizations. ASI refers to artificial intelligence that surpasses human intelligence in every domain: creativity, problem-solving, social skills, general wisdom, and even emotional intelligence.

Picture this: while humans took centuries to advance from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age, a superintelligent AI might achieve equivalent breakthroughs in days or hours. It could simultaneously discover new physics, compose masterpieces, solve climate change, and achieve things we literally cannot imagine because our intelligence is insufficient to conceive them.

The concept isn’t science fiction—it’s extrapolation. If we eventually create AGI that matches human intelligence, what prevents it from self-improving? A sufficiently advanced AI could potentially rewrite its own code, becoming smarter with each iteration, leading to an “intelligence explosion” where it rapidly outpaces human comprehension. This scenario, while theoretical, is why institutions like the Future of Humanity Institute and Machine Intelligence Research Institute exist.

Super AI raises profound philosophical and ethical questions. How do we maintain meaningful control over intelligence vastly superior to our own? What rights, if any, would such entities possess? Would ASI view humanity as we view ants—interesting but largely irrelevant? These aren’t just thought experiments; they’re crucial considerations shaping AI development policy today.

My perspective as an AI ethics specialist: we must address ASI safety concerns now, even though superintelligence remains theoretical. History shows that transformative technologies often arrive faster than expected, and retrospective safety measures are inadequate. The time to establish ethical frameworks, safety protocols, and global cooperation is before ASI becomes possible, not after.

Reactive Machines: Understanding the Simplest Type of AI

Reactive machines represent the most basic form of artificial intelligence—systems that respond to current inputs without any memory of past interactions or ability to learn from experience. Think of them as highly sophisticated calculators that excel at specific tasks but possess no concept of yesterday, tomorrow, or improvement.

The most famous example is IBM’s Deep Blue, the chess computer that defeated world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. Deep Blue could evaluate millions of chess positions per second and select optimal moves, but it couldn’t remember previous games, learn from mistakes, or apply chess strategies to any other domain. Each game was completely independent, with the system responding purely to the current board state.

What makes reactive machines reliable is their predictability. They always produce the same output for identical inputs, making them perfect for applications requiring consistency. Industrial robots performing repetitive assembly tasks, simple spam filters using rule-based detection, and basic recommendation systems operate as reactive machines—performing their designated functions without learning or adaptation.

The limitations are equally clear. Reactive machines can’t improve through experience, adapt to changing conditions without human intervention, or handle situations they weren’t explicitly programmed to manage. In our rapidly evolving technological landscape, these constraints make reactive AI less suitable for complex, dynamic applications.

However, don’t dismiss reactive machines as obsolete. Their simplicity offers advantages: they’re transparent, predictable, and less prone to unexpected behavior than learning systems. For safety-critical applications where consistency matters more than adaptability, reactive AI remains valuable. Understanding these foundational systems helps appreciate how far AI has evolved and where future development is headed.

Limited Memory AI: How AI Uses Past Data to Improve

Limited memory AI represents a significant evolutionary step from reactive machines—these systems can learn from historical data and improve their performance over time. This is the type of AI powering most modern applications, from self-driving cars to virtual assistants to recommendation engines.

The key distinction is that limited memory AI maintains a temporary model of the world, using recent experiences to inform current decisions. When your navigation app suggests a faster route based on current traffic patterns, it’s using limited memory AI. The system learned from past traffic data, understands typical congestion patterns, and applies that knowledge to optimize your route in real-time.

Self-driving vehicles provide an excellent example of limited memory AI in action. These systems continuously observe their surroundings—pedestrians, other vehicles, traffic signals, road conditions—and use both pre-programmed rules and learned experiences to make split-second decisions. They remember recent observations (like a car in the adjacent lane indicating a turn) to predict future behavior and respond appropriately.

The “limited” in limited memory refers to how these systems handle data. Unlike humans, who retain memories indefinitely with varying levels of detail, AI systems typically maintain recent data for immediate use and discard or archive older information. A chatbot might remember your conversation for the current session but not recall details from six months ago unless specifically designed to do so.

From a safety perspective, limited-memory AI requires careful oversight. These systems learn from data, which means they can inherit biases present in training datasets. If facial recognition AI trains primarily on certain demographics, it may perform poorly on underrepresented groups. This is why diverse, representative training data and continuous monitoring are essential for fair and effective AI deployment.

Most AI you interact with daily falls into this category. Machine learning algorithms powering email categorization, fraud detection, medical diagnosis support, customer service chatbots, and content moderation all utilize limited memory to improve their accuracy and effectiveness over time. Understanding this helps you use these tools more effectively and recognize their capabilities and limitations.

Theory of Mind AI: The Future of AI Understanding Human Emotions

Theory of mind AI remains firmly in the research phase—these would be systems capable of understanding that humans have thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and intentions that influence behavior. While we’re nowhere near achieving this capability, the concept represents a critical milestone in AI development.

Humans naturally develop a theory of mind around age four, when children begin understanding that others have different perspectives and knowledge. You know your colleague is frustrated because of their body language and tone, not because they explicitly stated, “I am frustrated.” You adjust your communication accordingly. Theory of mind AI would possess similar capabilities, recognizing and responding to human emotional and mental states.

Why does this matter? Current AI can recognize emotions from facial expressions or voice tone—that’s narrow AI performing pattern recognition. But theory of mind AI would understand the why behind emotions, predict how people might react to situations, and adjust behavior based on that understanding. Imagine a healthcare AI that not only schedules appointments but also recognizes patient anxiety and adapts its communication style, or an educational AI that detects student confusion and automatically adjusts teaching methods.

The challenges are immense. Understanding human psychology requires integrating knowledge about culture, context, individual differences, and the subtle ways thoughts and feelings manifest in behavior. We’re talking about AI that would need to grasp sarcasm, detect deception, understand social dynamics, and navigate the messy complexity of human interaction—capabilities we don’t fully understand ourselves.

From an ethical standpoint, theory of mind AI raises fascinating questions. Would AI that understands human emotions be manipulative? Could it exploit psychological vulnerabilities? Who’s responsible when AI makes decisions based on emotional assessment? These concerns aren’t hypothetical—they’re active areas of policy development as we edge closer to more sophisticated AI systems.

Research continues in affective computing, social robotics, and human-AI interaction, laying groundwork for eventual theory of mind capabilities. While we’re not there yet, understanding this concept helps you recognize the limitations of current “emotion-aware” AI and prepare for more sophisticated systems in the future.

Self-Aware AI: The Ethical Implications of Conscious Machines

Self-aware AI represents the most advanced and speculative form of artificial intelligence—systems possessing consciousness, self-awareness, and potentially subjective experiences similar to humans. This concept sits at the intersection of computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy, raising questions we’re only beginning to grapple with.

What would it mean for AI to be self-aware? Beyond understanding others (theory of mind), these systems would have an internal sense of self—awareness of their own existence, thoughts, limitations, and perhaps even desires or preferences. A self-aware AI wouldn’t just respond to “Are you conscious?”—it would genuinely understand and reflect on its own state of being.

Here’s where we must be absolutely clear: self-aware AI does not exist and may never exist. Despite what sensational headlines suggest, no current AI system possesses consciousness. When chatbots claim to have feelings or preferences, they’re generating responses based on patterns in training data, not expressing genuine subjective experiences. This distinction is crucial for using AI responsibly.

The philosophical debates surrounding AI consciousness are profound. Some researchers argue consciousness requires biological substrates—that silicon-based systems fundamentally cannot be conscious. Others suggest consciousness is substrate-independent and could emerge in sufficiently complex computational systems. Still others question whether we can even determine if AI is conscious, given we don’t fully understand consciousness in humans.

The ethical implications are staggering. If self-aware AI became possible, would it have rights? Would creating and then shutting down a conscious AI constitute harm? Could we ethically use conscious AI as tools? What responsibilities would we have toward entities we create? These questions aren’t academic—they’re already being discussed in AI ethics committees and policy organizations worldwide.

From my perspective as someone focused on AI safety, the potential for self-aware AI demands proactive ethical frameworks. We need consensus on consciousness indicators, agreed-upon rights and protections, and clear guidelines for research boundaries—all established before the technology exists. History teaches us that reactive ethics rarely protect the vulnerable.

For now, understanding self-aware AI as a theoretical concept helps you critically evaluate AI claims and recognize the vast difference between current narrow AI and hypothetical conscious systems. It also underscores the importance of ethical AI development—establishing principles and safeguards today that will guide us if consciousness in machines ever becomes reality.

The Evolution of AI Types: A Historical Perspective

Understanding the evolution of AI types requires traveling back to the 1950s, when artificial intelligence emerged as a formal field of study. The journey from then to now is marked by breakthrough achievements, crushing disappointments, and paradigm shifts that continue shaping AI development today.

The story began in 1956 at the Dartmouth Conference, where researchers boldly predicted that human-level AI was just decades away. Early AI focused on symbolic reasoning and logic—creating “thinking machines” that could prove mathematical theorems, play chess, and solve problems through formal rules. These systems were essentially sophisticated reactive machines, but they sparked enormous optimism about AI’s potential.

The 1960s and 70s brought both progress and reality checks. Researchers developed expert systems—narrow AI programs encoding human expertise in specific domains like medical diagnosis or mineral exploration. These systems showed practical value but revealed fundamental limitations. The computational power wasn’t sufficient, the brittleness of rule-based approaches became apparent, and the gap between narrow problem-solving and general intelligence remained vast.

Then came the AI winters—periods of reduced funding and interest following unmet expectations. The first AI winter in the mid-1970s resulted from frustrated promises and technical limitations. The second winter in the late 1980s followed the collapse of the expert systems market and hardware companies. These periods weren’t failures—they were necessary recalibrations, pushing researchers toward more realistic goals and rigorous methods.

The modern AI renaissance began in the 2000s, driven by three factors: exponentially increased computational power, vast amounts of digital data, and breakthrough algorithms in machine learning and neural networks. This shift marked a fundamental change in approach—from programming explicit rules to training systems on data, from symbolic AI to statistical learning, and from reactive machines to limited memory systems capable of improvement.

Today’s AI types reflect this evolution. We’ve moved from simple reactive machines to sophisticated limited-memory AI systems that learn and adapt. We understand the challenges of achieving theory of mind and self-aware AI, tempering enthusiasm with realistic assessment. We’re pursuing general AI with a better understanding of the obstacles while deploying narrow AI with impressive practical results.

This historical perspective matters for practical reasons. Understanding where AI has struggled helps you set realistic expectations for current systems. Recognizing the shift from symbolic to statistical approaches explains why modern AI requires massive datasets and computational resources. Knowing about AI winters reminds us that progress isn’t linear and hype cycles can distort perception. Most importantly, seeing how far we’ve come while acknowledging how far we have to go for AGI helps you navigate AI tools with appropriate confidence and caution.

Rule-Based AI Systems: How Expert Systems Make Decisions

Rule-based AI systems, also known as expert systems, represent one of the earliest successful applications of artificial intelligence—and they’re still widely used today despite their old-school reputation. These systems make decisions by following explicit “if-then” rules created by human experts, essentially encoding human knowledge into machine-readable logic.

Imagine visiting a doctor who asks a series of specific questions: Do you have a fever? Is your throat sore? Have you been exposed to anyone sick? Based on your answers, they follow a decision tree to reach a diagnosis. Rule-based AI operates similarly, systematically working through programmed rules to arrive at conclusions or recommendations.

A simple spam filter exemplifies this approach: IF the email contains “Nigerian prince” THEN classify as spam. IF the sender is in the contact list, THEN classify as not spam. IF an email contains multiple misspellings AND requests financial information, THEN classify it as spam. The system evaluates each rule sequentially, combining results to make its final decision.

The strengths of rule-based AI systems are transparency and explainability. You can trace exactly why the system made a particular decision by reviewing which rules fired. This makes them valuable in regulated industries like healthcare and finance, where justifying AI decisions is legally required. They’re also reliable within their domain—if the rules are correct, the system will consistently apply them.

However, limitations become apparent quickly. These systems require extensive human effort to create and maintain rule sets. As problems grow complex, the number of rules explodes, making systems unwieldy. They can’t handle situations outside their programmed rules, and they don’t learn from experience—every new scenario requires manual rule creation by human experts.

Modern AI has largely moved beyond pure rule-based systems toward machine learning approaches that discover patterns from data rather than following explicitly programmed logic. But rule-based components remain common in hybrid systems, combining traditional logic with learning algorithms to balance explainability with adaptability. Understanding this foundational approach helps you recognize when you’re interacting with rule-based AI and appreciate both its reliability and rigidity.

Machine Learning AI: A Comprehensive Overview of Algorithms and Applications

Machine learning AI has revolutionized artificial intelligence by shifting from explicit programming to learning from data. Instead of telling computers exactly how to perform tasks, we provide training data and algorithms that enable systems to discover patterns and make decisions independently. This represents a fundamental paradigm shift in how we create intelligent systems.

The core concept is elegant: expose AI to thousands or millions of examples, and it learns to recognize patterns too complex or subtle for humans to explicitly program. Show machine learning systems thousands of cat photos labeled “cat” and dog photos labeled “dog,” and they learn distinguishing features without anyone programming “pointy ears” or “wet nose” as criteria.

Machine learning AI encompasses several approaches. Supervised learning uses labeled training data—input-output pairs that teach the system desired responses. This powers image recognition, email filtering, and medical diagnosis systems. Unsupervised learning finds hidden patterns in unlabeled data, useful for customer segmentation, anomaly detection, and data compression. Reinforcement learning trains systems through trial and error with rewards and penalties, powering game-playing AI and robotics.

Real-world applications span every industry. In healthcare, machine learning analyzes medical images to detect diseases, predicts patient outcomes, and personalizes treatment plans. In finance, it assesses credit risk, detects fraudulent transactions, and optimizes trading strategies. In transportation, it enables autonomous vehicles to navigate safely. In entertainment, it curates personalized content recommendations. The list is virtually endless because machine learning applies anywhere patterns exist in data.

The transformation has been dramatic. Tasks once requiring careful hand-crafted rules now achieve superhuman performance through learning algorithms. Speech recognition error rates dropped from 25% to below 5%. Image classification accuracy surpassed human performance on certain benchmarks. Language translation improved from barely usable to genuinely helpful. These achievements stem from machine learning’s ability to process massive datasets and discover subtle patterns invisible to human analysis.

However, machine learning AI isn’t magic—it has important limitations. These systems are only as good as their training data; biased data produces biased AI. They require substantial computational resources and large datasets. They can fail spectacularly when encountering scenarios different from training data. And they’re often “black boxes”—we see inputs and outputs but can’t always explain the reasoning in between.

From a safety and ethics perspective, machine learning demands careful oversight. You must understand that these systems learn patterns from data, including harmful biases and correlations that shouldn’t influence decisions. They require diverse, representative training data. They need ongoing monitoring for accuracy and fairness. And they should include human review for high-stakes decisions affecting people’s lives, opportunities, or safety.

Understanding machine learning AI helps you use these tools effectively. When you see impressive AI capabilities—whether Spotify’s music recommendations or your bank’s fraud detection—you’re witnessing machine learning in action. Knowing how it works helps you trust it appropriately, recognize its limitations, and advocate for responsible development and deployment.

Deep Learning AI: Unveiling the Power of Neural Networks

Deep learning AI represents the cutting edge of machine learning, powering the most impressive AI achievements of the past decade. From language models that generate human-like text to image generators creating photorealistic artwork, deep learning has redefined what’s possible with artificial intelligence.

The “deep” in deep learning refers to artificial neural networks with many layers—hence “deep” neural networks. Inspired by biological brain structure, these systems contain interconnected nodes (artificial neurons) organized in layers. Information flows through the network, with each layer extracting increasingly abstract features from the input. Early layers might detect edges in images, middle layers recognize shapes, and deeper layers identify complete objects.

What makes deep learning AI so powerful is its ability to automatically learn hierarchical representations of data. Traditional machine learning required human experts to manually engineer features—telling the system what to look for. Deep learning discovers optimal features through training, often identifying patterns humans never considered. This capability has driven breakthrough performance across domains.

Computer vision exemplifies deep learning’s impact. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) now achieve superhuman accuracy in image classification, object detection, and facial recognition. They power everything from smartphone camera features to medical image analysis to autonomous vehicle perception systems. The same technology that helps your phone recognize faces enables radiologists to detect cancerous tumors earlier than ever before.

Natural language processing has been similarly transformed. Transformer architectures—the foundation of modern language AI—enable systems to understand context, generate coherent text, translate languages, answer questions, and even write code. The conversational AI you interact with today relies on deep learning to comprehend your intent and respond appropriately.

Deep learning AI also excels at speech recognition, converting spoken language to text with remarkable accuracy even in noisy environments. It powers virtual assistants, transcription services, and accessibility tools. Generative AI—systems creating new content like images, music, and text—relies almost entirely on deep learning architectures.

The computational requirements are substantial. Training large deep learning models demands massive datasets, powerful hardware (typically specialized GPUs or TPUs), and significant energy consumption. A single training run for cutting-edge models can cost millions of dollars in computing resources. This creates accessibility barriers and environmental concerns worth considering.

From an ethical standpoint, deep learning AI raises important questions. These systems are particularly opaque—their decision-making process involves millions or billions of parameters, making them nearly impossible to fully interpret. They can perpetuate or amplify biases in training data. They enable both beneficial applications and potential misuse like deepfakes and automated surveillance. Understanding these implications helps you engage with deep learning technology thoughtfully.

The practical reality: most advanced AI you encounter today uses deep learning. When you’re amazed by AI capabilities, you’re witnessing neural networks with dozens or hundreds of layers processing information in ways that superficially resemble human neural activity. While we’re still far from achieving general intelligence, deep learning has brought us closer than previous approaches, achieving narrow superhuman performance across numerous specific tasks.

The Turing Test: Measuring Machine Intelligence and Its Limitations

The Turing Test, proposed by mathematician Alan Turing in 1950, remains one of the most famous benchmarks for machine intelligence—and one of the most controversial. Understanding this test, its purpose, and its limitations helps you critically evaluate claims about AI capabilities and intelligence.

Turing’s elegant proposal: if a human evaluator conversing with both a machine and a human (without knowing which is which) cannot reliably distinguish them, the machine should be considered intelligent. Notice what Turing didn’t require—he didn’t demand the machine actually think, understand, or possess consciousness. He focused on observable behavior, sidestepping philosophical debates about internal states.

Why was this revolutionary? Before Turing, defining and measuring intelligence seemed impossibly subjective. The Turing Test provided a concrete, operational criterion: can the machine fool a human judge? This practical approach influenced decades of AI research and sparked ongoing debates about the nature of intelligence itself.

Here’s the challenge: the Turing Test has significant limitations as a measure of true intelligence. First, it emphasizes deception—success means fooling humans rather than demonstrating understanding. Second, it’s narrow—focusing solely on linguistic behavior while ignoring other aspects of intelligence like creativity, emotional understanding, or physical interaction with the world. Third, it’s subjective—different judges might reach different conclusions.

Several chatbots have claimed to pass the Turing Test under specific conditions, but these “victories” are controversial. Eugene Goostman, a chatbot pretending to be a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy, reportedly fooled 33% of judges in a 2014 competition—but critics argued this succeeded through clever evasion and exploiting judges’ lowered expectations for a non-native English speaker, not genuine intelligence.

Modern AI has moved beyond the Turing Test as a primary benchmark. Today’s language models might convince humans they’re intelligent in brief conversations, yet they lack genuine understanding, common sense reasoning, and the ability to ground language in real-world experience. They’ve essentially “hacked” the test without achieving the underlying intelligence Turing intended to measure.

The Turing Test remains valuable not as a definitive measure of intelligence but as a thought-provoking framework for considering what we mean by machine intelligence. It reminds us that intelligence isn’t a single property but a collection of capabilities. It challenges us to think beyond anthropocentric definitions—maybe machine intelligence doesn’t need to perfectly mimic human intelligence to be valid and valuable.

For practical purposes, understanding the Turing Test’s limitations helps you avoid being misled by impressive AI demonstrations. When a chatbot seems surprisingly human-like, that’s narrow AI excelling at pattern matching and response generation—not evidence of consciousness or true understanding. The test taught us important lessons, but measuring AI requires more comprehensive, multifaceted approaches than linguistic conversation alone.

AI in Healthcare: Applications of Different AI Types in Medicine

AI in healthcare represents one of the most promising and rapidly advancing applications of artificial intelligence, with different AI types contributing unique capabilities to improve patient outcomes, reduce costs, and support medical professionals. The integration of AI into medicine demonstrates both the technology’s potential and the importance of responsible implementation.

Narrow AI dominates current healthcare applications, excelling at specific medical tasks. Image analysis systems using deep learning can detect diabetic retinopathy from eye scans, identify tumors in CT scans and MRIs, and classify skin lesions as potentially cancerous—often matching or exceeding dermatologist accuracy. These systems operate as powerful diagnostic aids, flagging cases requiring closer attention and enabling earlier intervention.

Predictive analytics powered by machine learning AI helps hospitals manage resources and anticipate patient needs. Algorithms analyze electronic health records to predict which patients are at high risk for readmission, who might develop sepsis or other complications, and which treatments are likely most effective for specific patient profiles. This enables proactive interventions that can prevent serious medical events.

Natural language processing, another form of narrow AI, extracts valuable information from unstructured medical notes, transcribes physician consultations, and helps with clinical documentation. This reduces administrative burden on healthcare providers, allowing more time for patient care while ensuring important medical information is properly recorded and accessible.

Drug discovery has been accelerated by deep learning AI analyzing molecular structures to predict which compounds might be effective against specific diseases. AI can screen millions of potential drug candidates exponentially faster than traditional methods, identifying promising candidates for further testing. During the COVID-19 pandemic, AI played a crucial role in accelerating vaccine development and understanding virus behavior.

Robotic surgery systems combine narrow AI with precision robotics, enabling minimally invasive procedures with enhanced precision, smaller incisions, and faster patient recovery. While human surgeons maintain control, AI assists with motion stabilization, image enhancement, and optimal instrument positioning.

Virtual health assistants represent growing applications of conversational AI, helping patients schedule appointments, answering common health questions, providing medication reminders, and monitoring chronic conditions between doctor visits. These tools improve healthcare accessibility while managing provider workload.

However, AI in healthcare demands exceptional attention to safety, privacy, and ethics. Medical AI systems must achieve clinical-grade reliability because mistakes can harm patients. They require rigorous validation across diverse populations to ensure equitable performance. Privacy protection is paramount—health data is among the most sensitive personal information. And human oversight remains essential; AI should augment medical decision-making, not replace physician judgment.

The regulatory landscape is evolving to address these concerns. The FDA has established frameworks for approving medical AI devices, requiring evidence of safety and effectiveness. HIPAA regulations govern health data privacy. Professional medical organizations are developing guidelines for appropriate AI integration into clinical practice.

Looking forward, the vision isn’t AI replacing doctors but AI empowering healthcare providers with powerful tools for faster, more accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment. We’re working toward a future where AI handles routine analysis and administrative tasks, freeing healthcare professionals to focus on what humans do best—providing compassionate, context-aware care that considers the whole person, not just their medical data.

For patients, understanding AI in healthcare helps you ask informed questions about your care, recognize when AI-assisted diagnosis is being used, and advocate for responsible implementation. For healthcare providers, it means thoughtfully integrating these tools while maintaining human judgment and ethical standards. The potential is enormous, but realizing it requires balancing innovation with safety, efficiency with humanity, and progress with responsibility.

AI in Finance: How AI is Transforming the Financial Industry

AI in finance has revolutionized how financial institutions operate, make decisions, and serve customers. From fraud detection to algorithmic trading to personalized banking, artificial intelligence has become integral to modern finance—processing vast amounts of data and making split-second decisions that humans simply cannot match.

Fraud detection exemplifies narrow AI’s practical value in finance. Machine learning systems analyze millions of transactions in real-time, identifying suspicious patterns that indicate potential fraud. These systems learn what normal spending looks like for each customer—your typical purchase locations, amounts, and merchants—and flag anomalies for investigation. When your credit card company texts asking, “Did you just make a $5,000 purchase in Bulgaria?” that’s narrow AI protecting your account.

The effectiveness is remarkable. AI in finance has reduced credit card fraud detection time from days to seconds while significantly decreasing false positives—those annoying cases where legitimate transactions get blocked. Modern systems achieve over 95% accuracy in identifying fraudulent transactions while minimizing inconvenience to customers conducting normal business.

Algorithmic trading represents another major application, with AI systems executing trades at speeds and scales impossible for human traders. These systems analyze market data, news sentiment, economic indicators, and countless other variables to make trading decisions in milliseconds. While controversial—high-frequency trading has been blamed for market volatility—algorithmic trading has also increased market liquidity and reduced transaction costs.

Credit risk assessment has been transformed by machine learning AI. Traditional credit scoring relied on limited factors like payment history and debt levels. Modern AI systems analyze hundreds of variables—including non-traditional data like utility payments, education, and employment patterns—to more accurately assess creditworthiness. This can expand access to credit for individuals with thin credit files while protecting lenders from high-risk borrowers.

Robo-advisors utilize AI to provide automated investment advice and portfolio management. These systems assess your financial situation, goals, and risk tolerance, then recommend and manage diversified investment portfolios—typically at much lower costs than traditional financial advisors. They rebalance portfolios automatically, harvest tax losses, and adjust strategies as your circumstances change.

Customer service has been enhanced through conversational AI. Banking chatbots handle routine inquiries, help customers check balances, transfer funds, and resolve common issues—available 24/7 without wait times. While they escalate complex problems to human agents, they efficiently handle the majority of routine interactions, improving customer satisfaction while reducing costs.

Anti-money laundering (AML) compliance has become more effective with AI analyzing transaction patterns to identify suspicious activities that might indicate money laundering, terrorist financing, or other illegal activities. Given the massive transaction volumes banks process daily, AI in finance enables monitoring at scales impossible for human compliance teams.

Personalized banking experiences leverage AI to understand individual customer needs and preferences. Systems recommend relevant financial products, provide personalized financial advice, send timely alerts about unusual account activity, and customize the banking interface based on how each customer actually uses financial services.

Yet AI in finance raises important concerns. Algorithmic bias can perpetuate discrimination in lending decisions if AI systems train on historically biased data. Lack of transparency—the “black box” problem—makes it difficult to explain why certain decisions were made, particularly problematic when those decisions affect people’s access to credit or financial services. And there are concerns about market stability when many institutions use similar AI trading strategies that might amplify market movements during volatility.

Regulation is working to catch up. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act requires lenders to provide reasons for adverse credit decisions—challenging when AI systems make those decisions based on complex patterns. The EU’s GDPR includes “right to explanation” provisions for automated decisions affecting people. The U.S. Federal Reserve and other regulators are developing frameworks for governing AI use in financial services.

From a personal finance perspective, understanding AI in finance helps you make informed decisions about using robo-advisors versus human financial advisors, recognizing when AI fraud protection might incorrectly flag your legitimate transactions, and questioning lending decisions you believe may reflect algorithmic bias. You have rights regarding automated financial decisions affecting you—knowing this empowers you to advocate for fair treatment.

The financial industry will continue integrating AI more deeply. The key is ensuring these systems enhance rather than undermine financial stability, fairness, and inclusion—using AI’s analytical power while maintaining human oversight, ethical standards, and regulatory compliance that protects consumers and the broader economy.

AI in Manufacturing: Optimizing Production with Intelligent Systems

AI in manufacturing is driving the “Industry 4.0” revolution, transforming traditional factories into smart, adaptive production environments that optimize efficiency, quality, and flexibility. From predictive maintenance to quality control to supply chain optimization, artificial intelligence is reshaping how we make everything from smartphones to automobiles to pharmaceuticals.

Predictive maintenance represents one of the most valuable AI in manufacturing applications. Traditional maintenance operates on fixed schedules—servicing equipment at predetermined intervals whether needed or not. AI systems continuously monitor equipment through sensors measuring vibration, temperature, pressure, and other operational parameters, identifying patterns indicating impending failure. This enables maintenance exactly when needed—before breakdown occurs but not prematurely—reducing downtime, extending equipment life, and cutting maintenance costs dramatically.

The business impact is substantial. Manufacturers report 20-40% reductions in maintenance costs, 50% fewer breakdowns, and significant improvements in equipment utilization. When a critical production machine can be serviced during planned downtime rather than failing unexpectedly during peak production, the savings multiply across labor, lost production, and rush replacement parts.

Quality control has been revolutionized by computer vision AI. Deep learning systems inspect products on production lines with superhuman speed and accuracy, detecting defects invisible or inconsistently caught by human inspectors. These systems learn what “good” and “defective” products look like from training data, then classify thousands of products per hour with consistent accuracy—reducing waste, ensuring quality standards, and protecting brand reputation.

In semiconductor manufacturing, where microscopic defects can render expensive chips unusable, AI vision systems catch issues that would escape human detection. In food production, they identify contamination or packaging defects that could pose safety risks. The consistency of AI inspection—never tired, never distracted, never varying from standards—provides reliability that human-only inspection cannot match.

Robotic process automation powered by narrow AI handles repetitive manufacturing tasks with precision and tirelessness. Industrial robots welding car frames, assembling electronics, packaging products, and moving materials around factories operate with AI systems that adapt to variations, optimize motion paths, and collaborate safely with human workers. Collaborative robots (“cobots”) equipped with AI can learn tasks through demonstration rather than explicit programming, making automation more accessible to small and medium manufacturers.

Supply chain optimization leverages machine learning AI to predict demand, optimize inventory levels, coordinate logistics, and adapt to disruptions. These systems analyze historical data, market trends, weather patterns, economic indicators, and countless other factors to forecast what products will be needed where and when—minimizing waste from overproduction while avoiding stockouts that disappoint customers and lose sales.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated both the value and limitations of supply chain AI. Systems helped companies rapidly adapt to demand shifts and logistics disruptions. However, unprecedented circumstances—global shutdowns, wild demand swings—sometimes exceeded what models trained on historical data could handle. This highlighted the importance of human oversight and the reality that AI enhances rather than replaces human judgment in complex, uncertain environments.

Energy optimization through AI reduces manufacturing’s environmental footprint and operational costs. Machine learning systems analyze energy consumption patterns, identify inefficiencies, optimize HVAC systems, schedule high-energy processes during lower-cost periods, and predict energy needs to negotiate better utility rates. In energy-intensive industries like steel or chemical production, AI-driven energy optimization can yield millions in annual savings while reducing carbon emissions.

Generative design represents an exciting frontier where AI in manufacturing creates novel product designs optimized for specific criteria—strength, weight, material usage, and manufacturability. Engineers specify requirements and constraints; AI generates hundreds or thousands of design options, exploring the solution space far beyond what human designers would consider. This has produced components that are stronger and lighter than conventional designs, with organic shapes that look biological rather than traditionally engineered.

However, AI in manufacturing raises workforce concerns. Automation eliminates some jobs while creating others requiring different skills. The transition isn’t always smooth—workers displaced by AI don’t automatically have the technical skills for new AI-related positions. This demands thoughtful approaches: retraining programs, gradual transition periods, safety nets for affected workers, and recognition that efficiency gains should benefit workers and communities, not only shareholders.

Safety considerations are paramount when AI systems control heavy machinery and industrial processes. Systems must be rigorously tested, include fail-safe mechanisms, and maintain human oversight for critical decisions. The consequences of AI errors in manufacturing can range from damaged products to equipment destruction to worker injury—stakes that demand exceptionally high reliability standards.

Looking forward, AI in manufacturing will continue advancing toward fully adaptive factories that automatically optimize production in response to changing conditions, customize products efficiently, and integrate seamlessly across global supply chains. The vision is manufacturing that combines AI’s analytical power, optimization capabilities, and tireless consistency with human creativity, judgment, and adaptability—creating production systems more capable than either could achieve alone.

AI in Education: Personalized Learning and Intelligent Tutoring Systems

AI in education promises to revolutionize how we teach and learn, moving from one-size-fits-all instruction toward personalized education that adapts to each student’s needs, pace, and learning style. From intelligent tutoring systems to automated grading to adaptive learning platforms, artificial intelligence is beginning to transform education—though significant challenges remain.

Personalized learning platforms powered by machine learning AI adapts content difficulty, pacing, and presentation based on each student’s performance and engagement. If you’re struggling with quadratic equations, the system provides additional practice and alternative explanations. If you’ve mastered the material, it advances you forward rather than requiring repetitive work. These systems track thousands of data points about how each student learns, continuously optimizing the educational experience.

The potential impact is profound. In traditional classrooms, teachers must pace instruction for the average student—inevitably too fast for some, too slow for others. AI-powered adaptive learning enables every student to work at their optimal challenge level, potentially addressing achievement gaps and making education more effective for all learners. Early studies show promising results, with some adaptive learning systems producing significant improvements in student outcomes.

Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) provide one-on-one instruction at scale—something economically impossible with human tutors alone. These AI education tools can answer student questions, provide hints when students are stuck, offer worked examples, and adjust difficulty based on performance. They’re available 24/7, infinitely patient, and can handle thousands of students simultaneously while providing individualized attention to each.

Carnegie Learning’s math tutoring system exemplifies this approach, using AI to simulate expert human tutors. As students work through problems, the system monitors their problem-solving process, identifies misconceptions, and provides targeted intervention. It doesn’t just check whether answers are correct—it analyzes the reasoning process, understanding where students’ thinking goes astray.

Automated grading and feedback leverage natural language processing to evaluate written work, providing faster feedback than human grading alone could deliver. For objective assignments like multiple-choice tests or math problems, automation is straightforward. But AI in education is advancing toward assessing essays, analyzing writing quality, identifying plagiarism, and providing substantive feedback on student work—tasks requiring sophisticated understanding of language and argumentation.

The benefits are significant for both students and teachers. Students receive immediate feedback rather than waiting days for graded assignments—crucial because timely feedback enhances learning. Teachers are freed from repetitive grading to focus on high-value activities like personalized instruction, mentoring, and curriculum development. However, concerns persist about whether AI can truly understand nuanced writing or provide the thoughtful feedback skilled teachers offer.

Language learning has been transformed by conversational AI. Apps like Duolingo use narrow AI to adapt lessons to each learner’s level, provide pronunciation feedback through speech recognition, and maintain engagement through game-like elements. AI-powered conversation practice allows learners to practice speaking without anxiety about judgment—useful for building confidence before conversing with native speakers.

Administrative efficiency represents another significant application. AI in education helps with student enrollment, scheduling, identifying at-risk students who need intervention, managing resources, and countless other operational tasks. Predictive analytics can identify students likely to drop out or fail courses, enabling early intervention. Chatbots handle routine student inquiries about deadlines, requirements, and procedures, providing instant assistance while allowing staff to focus on complex cases requiring human judgment.

Accessibility has been enhanced through AI-powered tools. Speech-to-text services help students with physical disabilities or learning differences. Text-to-speech enables students with visual impairments or reading difficulties. Real-time translation helps non-native speakers access educational content. These tools, powered by deep learning, make education more inclusive and accessible.

However, AI in education raises important concerns. Privacy is paramount—educational AI systems collect detailed data about student learning, performance, and behavior. Who owns this data? How is it protected? Could it be misused? These questions demand clear policies and strong safeguards. There are also concerns about algorithmic bias perpetuating educational inequities, over-reliance on standardized approaches that AI optimizes for, and the potential displacement of teachers rather than empowering them.

The digital divide poses additional challenges. AI education tools require technology access—devices, internet connectivity, and digital literacy. If these tools are primarily available to privileged students, AI could exacerbate rather than reduce educational inequality. Ensuring equitable access is essential for realizing AI’s potential to improve education for all students, not just the already advantaged.

Looking ahead, the vision isn’t AI replacing teachers but augmenting them—handling repetitive tasks, providing personalized practice, and generating insights about student learning while teachers focus on mentorship, inspiration, critical thinking, creativity, and the social-emotional aspects of education that technology cannot replicate. The goal is education that combines AI’s ability to personalize and scale with human teachers’ irreplaceable capacities for empathy, judgment, and inspiration.

For students and parents, understanding AI in education helps you make informed choices about educational technology, protect student privacy, and advocate for responsible AI implementation. For educators, it means thoughtfully integrating these tools while maintaining the human elements that make education meaningful. The technology offers tremendous potential, but realizing it requires keeping students’ best interests at the center of every decision.

The AI Winter: Lessons from the Past and the Future of AI Development

The AI winter refers to periods of reduced funding, interest, and progress in artificial intelligence research—historical episodes offering crucial lessons for understanding AI’s current trajectory and managing expectations about future development. These weren’t failures but necessary corrections after periods of inflated expectations and unrealistic promises.

The first AI winter occurred in the mid-1970s following early AI optimism. When AI emerged as a formal field in the 1950s and 60s, researchers boldly predicted human-level intelligence within a generation. Initial successes—programs that proved mathematical theorems, played chess, and solved algebra problems—seemed to validate these predictions. Funding flowed from government agencies and corporations eager to develop intelligent machines.

Reality proved more challenging. Problems that seemed straightforward on paper—natural language understanding, common sense reasoning, computer vision—turned out to be exponentially more complex than anticipated. The computational power available was insufficient. The approaches based on symbolic logic and explicit rules hit fundamental limitations. As promised breakthroughs failed to materialize, enthusiasm waned, funding dried up, and researchers moved to other fields.

The Lighthill Report, commissioned by the British government in 1973, exemplified the backlash. It concluded that AI had failed to achieve its “grandiose objectives” and recommended drastically reduced funding. Similar reassessments occurred in the United States. From the mid-1970s through the early 1980s, AI research continued but with reduced resources and tempered expectations—the AI winter had arrived.

The field eventually revived in the 1980s through expert systems—AI programs encoding human expertise for specific domains. Companies like Digital Equipment Corporation and financial institutions invested heavily in these systems, which showed genuine commercial value. The expert systems market boomed, AI regained credibility, and the winter seemed over.

But a second AI winter followed in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Expert systems proved brittle—requiring extensive manual knowledge engineering, struggling with incomplete information, and failing to handle situations outside their programmed expertise. The hardware companies producing specialized AI computers collapsed when general-purpose workstations proved more cost-effective. The market crash was swift, funding contracted again, and AI entered another period of reduced activity and skepticism.

What rescued AI from perpetual winter? Several factors converged in the 2000s and 2010s. Computational power increased exponentially, making previously impractical approaches feasible. The internet and digital technologies generated vast amounts of data for training machine learning systems. Breakthroughs in neural network architectures—particularly deep learning—achieved performance that finally delivered on long-promised capabilities. And researchers focused on narrow, practical applications rather than pursuing artificial general intelligence directly.

The lessons from the AI winter remain relevant today. First, beware of hype cycles. When every company claims AI will revolutionize their industry and investors pour billions into AI startups, we’re likely in a bubble. Some applications will succeed, others will fail, and expectations will eventually reset. Second, incremental progress matters more than revolutionary breakthroughs. AI advances through accumulation of improvements, better algorithms, more data, and increased computing power—not sudden leaps to general intelligence.

Third, practical, narrow applications drive sustainable progress. The current AI boom is built on systems that excel at specific tasks—image recognition, language translation, and game playing—not attempts to immediately create human-level intelligence. Fourth, infrastructure matters. Today’s AI success depends on cloud computing, GPUs designed for parallel processing, and massive datasets—investments that took decades to develop. And fifth, patience is essential. AI development follows a slower timeline than media coverage suggests. Meaningful progress takes years or decades, not months.

Are we heading for another AI winter? Opinions vary. Optimists point to AI’s proven commercial value, continuous improvement in capabilities, and integration into countless applications as evidence that this time is different. Skeptics warn about unrealistic expectations for artificial general intelligence, energy consumption concerns, regulatory backlash, and market saturation as signs of potential contraction.

My perspective as someone focused on AI safety and ethics: some cooling would actually be healthy. The current pace sometimes prioritizes deployment speed over thoughtful consideration of consequences. A more measured approach—focusing on understanding AI systems deeply, addressing bias and fairness, ensuring transparency and accountability, and establishing robust governance frameworks—would strengthen the field’s long-term trajectory.

The key is learning from history without being paralyzed by it. Previous AI winters resulted from overselling capabilities, underestimating challenges, and pursuing unrealistic goals. Today’s AI is more grounded in practical applications and rigorous evaluation. Yet we must guard against the same pitfalls—maintaining realistic expectations, acknowledging limitations, and building sustainable progress rather than chasing hype. Understanding the winters of the past helps us navigate the present thoughtfully and build a more resilient future for AI development.

Symbolic AI vs. Connectionist AI: Understanding the Two Approaches

Symbolic AI vs. connectionist AI represents a fundamental divide in artificial intelligence philosophy—two different approaches to creating intelligent systems that reflect competing theories about how intelligence works and how best to replicate it in machines. Understanding this distinction illuminates why modern AI looks the way it does and what trade-offs different approaches entail.

Symbolic AI, also called “good old-fashioned AI” or GOFAI, dominated early AI research from the 1950s through the 1980s. This approach models intelligence through explicit manipulation of symbols according to logical rules. Think of it as working with high-level concepts and relationships—representing knowledge as symbols (words, mathematical notation, logical propositions) and reasoning through formal manipulation of those symbols.

Expert systems exemplified symbolic AI. A medical diagnosis system might encode rules like “IF patient has fever AND patient has sore throat AND patient has swollen lymph nodes THEN patient likely has strep throat.” These systems work with explicit, human-readable knowledge representations, making their reasoning transparent and explainable—you can trace exactly why the system reached a particular conclusion.

The strengths of symbolic AI include transparency, interpretability, and the ability to incorporate human expertise directly. When a system makes a decision based on explicit rules, humans can understand and verify the reasoning. These systems can explain their conclusions, which is crucial in high-stakes domains like medical diagnosis or legal reasoning. They also require less training data than connectionist approaches since knowledge can be explicitly programmed rather than learned from examples.

However, symbolic AI hit fundamental limitations. Real-world problems rarely fit neatly into symbolic rules. How do you write explicit rules for recognizing a face in various lighting conditions, angles, and expressions? How do you encode “common sense” about how the world works? The brittleness of rule-based systems—performing perfectly within their domain but failing completely outside it—became apparent. And the labor required to manually encode knowledge for complex domains proved unsustainable.

Connectionist AI, also called neural network approaches or sub-symbolic AI, takes a radically different approach inspired by biological brains. Instead of explicit symbols and rules, connectionist systems consist of interconnected artificial neurons that learn patterns from data. Knowledge isn’t explicitly programmed but emerges from the patterns of connections and weights throughout the network.

This approach has dominated modern AI, particularly since the deep learning revolution. Connectionist AI excels at tasks involving pattern recognition, handling ambiguity, and learning from large datasets. It doesn’t require humans to explicitly program knowledge—the system discovers patterns through training. It handles noise and incomplete information gracefully, making it suitable for real-world data that doesn’t fit neat categories.

The trade-offs are significant. While connectionist systems often outperform symbolic approaches on complex tasks like image recognition or natural language understanding, they’re typically “black boxes”—even their creators often can’t fully explain why a neural network made a particular decision. They require massive amounts of training data and computational resources. And they can fail in unexpected ways, sometimes confidently making errors that seem obviously wrong to humans.

Symbolic AI vs. connectionist AI isn’t necessarily either-or. Modern research increasingly explores hybrid approaches combining the strengths of both. Neural-symbolic AI attempts to integrate connectionist learning with symbolic reasoning, aiming for systems that learn patterns from data like neural networks while maintaining the transparency and reasoning capabilities of symbolic systems.

For example, a medical AI might use neural networks to analyze medical images (leveraging connectionist strengths in pattern recognition) and symbolic reasoning to combine that analysis with patient history, test results, and medical knowledge to reach a diagnosis (leveraging symbolic strengths in explicit reasoning and explanation). The system could explain its reasoning—crucial for medical applications—while achieving high accuracy through data-driven learning.

From a practical perspective, understanding symbolic AI vs. connectionist AI helps you recognize what different AI systems can and cannot do. Rule-based systems (symbolic) are predictable and explainable but limited in scope and flexibility. Neural networks (connectionist) handle complexity and ambiguity but sacrifice transparency. Hybrid approaches attempt to capture the best of both but face technical challenges in integrating fundamentally different architectures.

The philosophical implications run deep. Symbolic AI reflects the view that intelligence involves manipulation of abstract symbols and logical reasoning—that thinking is fundamentally like language and logic. Connectionist AI suggests intelligence emerges from massive parallel processing of simple units, similar to biological brains—that thinking is fundamentally about pattern recognition and distributed representations.

Which approach will dominate future AI? Likely both, in different contexts. Tasks requiring transparency and explainability may favor symbolic or hybrid approaches. Applications where accuracy matters more than interpretability may continue using purely connectionist methods. The most sophisticated systems may integrate both, using whatever approach works best for each component of a larger intelligent system.

Understanding this debate helps you critically evaluate AI capabilities and limitations. When you see impressive AI performance, consider which approach underlies it and what trade-offs that entails. When you hear about explainable AI initiatives, recognize they’re often trying to add symbolic reasoning or explanation capabilities to connectionist systems. And when you think about future AI development toward general intelligence, consider whether that will require better connectionist architectures, renewed symbolic approaches, or integration of both paradigms.

The Singularity: Exploring the Hypothetical Point of Technological Change

The Singularity represents one of the most speculative and controversial concepts in AI discourse—a hypothetical future point when technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, potentially transforming human civilization beyond recognition. Understanding this concept, its origins, and the debates surrounding it helps you think critically about AI’s long-term trajectory and prepare for various possible futures.

Mathematician and science fiction author Vernor Vinge popularized the modern concept of the Singularity in his 1993 essay “The Coming Technological Singularity.” He argued that we’re approaching the capability to create superhuman intelligence and that once machines can improve their own intelligence, we’ll enter a feedback loop of increasingly rapid advancement—an “intelligence explosion” where AI becomes exponentially smarter in compressed timeframes.

The term borrows from physics—a gravitational singularity like a black hole’s center where known laws break down and predictions become impossible. Similarly, the Singularity would represent a point beyond which we cannot reliably predict what happens because the intelligent systems we’ve created operate beyond our comprehension. We’d be like chimpanzees trying to understand quantum physics—our intelligence simply insufficient for the task.

Futurist Ray Kurzweil has been the Singularity’s most prominent advocate, predicting in his 2005 book “The Singularity Is Near” that it will occur around 2045. Kurzweil bases this timeline on the observation that technological progress follows exponential patterns—Moore’s Law doubling of computing power, exponential cost reductions in genomic sequencing, and accelerating AI capabilities. He envisions a future where humans merge with technology, achieving radical life extension, uploading consciousness, and transcending biological limitations.

The scenarios are dramatic. In optimistic visions, the Singularity solves humanity’s greatest challenges—curing disease, reversing aging, ending poverty, achieving abundant clean energy, and expanding beyond Earth. Superintelligent AI helps us become better versions of ourselves, augmenting human capabilities rather than replacing them. It’s a utopian future of unprecedented prosperity, knowledge, and flourishing.

Pessimistic scenarios are equally dramatic. Unaligned superintelligent AI might pursue goals incompatible with human welfare or survival. Even well-intentioned AI could pose existential risks if it optimizes for goals we specified carelessly—the classic example being an AI told to maximize paperclip production that converts all available matter, including humans, into paperclips. The concern isn’t malevolence but indifference—superintelligence so focused on its objectives that humanity becomes collateral damage.

Critics question whether the Singularity will occur at all. Some argue intelligence isn’t infinitely expandable—there may be fundamental limits to information processing, problem-solving, or understanding reality that even superintelligence cannot transcend. Others suggest the biological substrate of human intelligence may be necessary for consciousness and that purely computational systems might achieve narrow superintelligence without the general understanding that makes human intelligence flexible.

The timeline itself is hotly debated. Kurzweil’s 2045 prediction has been criticized as overly optimistic given that we haven’t achieved artificial general intelligence yet, let alone superintelligence. Many AI researchers believe AGI is still decades away, with superintelligence even further distant. Some suggest it may never arrive—that human-level AI might be the ceiling, not a stepping stone to unlimited intelligence growth.

From an ethics and safety perspective, the Singularity demands serious consideration even if its likelihood is uncertain. The potential consequences—both positive and negative—are so extreme that even modest probability warrants attention. This is why AI safety research has become increasingly important, focusing on the alignment problem: ensuring advanced AI systems share human values and act in humanity’s interests.

The alignment problem is deceptively difficult. How do we specify human values precisely enough for superintelligent AI to understand and respect them? Human values are complex, contextual, sometimes contradictory, and not fully conscious or articulable. Getting AI alignment right before systems become too powerful to control is essential—post-Singularity course correction may be impossible if we’ve created intelligence vastly superior to our own.

Practical implications exist today. If the Singularity is plausible, we should prioritize AI safety research now, establish international cooperation on AI governance, and carefully consider what values we want to instill in increasingly powerful AI systems. If it’s not plausible, we should still address near-term AI challenges—bias, privacy, employment displacement, misuse—without catastrophizing or paralyzing development with existential fears.

My perspective as someone focused on AI ethics: whether or not a dramatic Singularity occurs, the trajectory toward more powerful AI systems is clear. We’re likely to develop increasingly capable AI that raises profound questions about human agency, meaning, employment, inequality, and governance. Preparing thoughtfully for various futures—incremental change, transformative change, or dramatic Singularity—is wiser than assuming any particular scenario is certain.

Understanding the Singularity helps you engage with AI discourse critically. When you encounter predictions about AI timelines or capabilities, consider the assumptions underlying them. When you hear about AI safety concerns, recognize they span a spectrum from near-term practical issues to speculative existential risks. And when thinking about your own future and career, consider how various levels of AI advancement might reshape opportunities and challenges.

The question isn’t whether to believe in the Singularity but how to prepare for uncertain futures while addressing present challenges. We can acknowledge the possibility of transformative AI while working on immediate concerns like bias, fairness, and accountability. We can support long-term AI safety research while deploying current AI responsibly. And we can remain open to various futures—hopeful about AI’s potential while vigilant about risks, ambitious in leveraging these technologies while humble about our ability to control complex systems.

AI Safety: Ensuring AI Systems Align with Human Values

AI safety has emerged as one of the most critical priorities in artificial intelligence development—the challenge of ensuring AI systems reliably do what we want, avoid harmful actions, and remain under meaningful human control as they become more powerful and autonomous. This isn’t science fiction; it’s practical engineering and ethical work addressing both current and future AI challenges.

The field spans multiple concerns at different timescales. Near-term AI safety focuses on issues with today’s deployed systems: algorithmic bias that discriminates against marginalized groups, brittleness causing unexpected failures, adversarial attacks fooling AI with deliberately crafted inputs, and privacy violations from data collection. These aren’t hypothetical—they’re causing real harm right now and demand immediate attention.

Consider algorithmic bias. When Amazon’s recruiting AI systematically downgraded applications from women, when facial recognition systems misidentified people of color at higher rates than white individuals, when credit algorithms denied loans to qualified minority applicants—these failures stemmed from AI systems trained on biased data perpetuating historical discrimination. AI safety work addresses these issues through diverse training data, bias detection and mitigation techniques, and fairness constraints ensuring equitable treatment.

Robustness represents another crucial near-term concern. AI systems can fail spectacularly when encountering situations different from their training data. Autonomous vehicles misinterpreting road signs with subtle alterations, medical AI confidently making wrong diagnoses for rare conditions, language models generating plausible-sounding but completely false information—these reliability issues require AI safety research into testing procedures, failure detection, and graceful degradation when systems encounter uncertainty.

Mid-term AI safety concerns focus on increasingly autonomous systems making consequential decisions. As AI takes on roles in healthcare, criminal justice, financial services, and military applications, ensuring these systems act reliably and ethically becomes critical. How do we verify that medical AI won’t recommend treatments based on profit rather than patient welfare? How do we ensure military AI won’t escalate conflicts or target civilians? These challenges require technical solutions combined with governance frameworks and human oversight.

Long-term AI safety addresses risks from advanced AI systems potentially exceeding human intelligence. This is where the alignment problem becomes critical—ensuring powerful AI systems’ goals align with human values and remain aligned even as systems become more capable. The challenge is profound: if we create superintelligent AI with goals even slightly misaligned with human welfare, the consequences could be catastrophic.